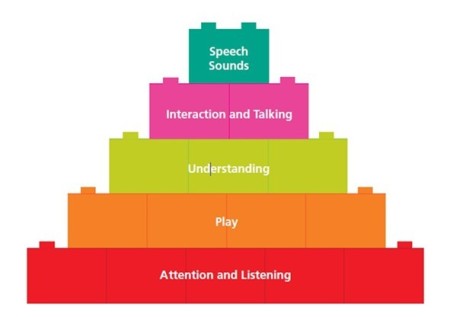

We can think of the skills children need to develop their language, speech, social interaction and communication skills as building blocks. The skills build on each other to enable children to add the next block or skill as they develop. We can think of these blocks as building a pyramid with foundation skills at the bottom and more advanced skills higher up. If one of the building blocks is missing or is not as strong as we expect, this can have an effect on the other skills because they are all interlinked or dependant on each other.

For example, the development of speech sounds is at the very top of the pyramid, but in order to develop this, there needs to be good attention and listening, and practice during conversations in place, and they must understand the words they are trying to produce. Speech Therapists work with children who might be struggling with any of these areas:

The following websites have more information about how speech and language skills develop:

Ages and stages - Speech and Language UK: Changing young lives

Encouraging early development in babies and young children

There are so many things we can do to help our children on the road to talking.

Here are some of our top tips to try:

-

Follow the child’s lead – focus on the things they are interested in

-

WAIT! Add pauses after your comments or questions – young children’s brains take longer to process information

-

Copy what the child does or says – then wait for them to respond

-

Try not to ask too many questions – try commenting on what the child is doing instead

-

Help children understand new words, by using words to match their interests and repeating them over and over again

-

Say the words you think the child is trying to say, or would say if they could – hearing it from you will help them to have a go next time

Babies make sounds right from the time they are born – in fact, they announce their arrival with a loud cry! During the first six months, babies learn to make other sounds besides crying, such as cooing and laughing..

Then, between approximately five to 10 months of age, babies’ sounds start to change. They begin to make syllables, such as “ba ba” or “di di” that include a consonant and a vowel. This is known as BABBLING.

As babies continue to develop, their babbling begins to sound more and more like conversation. This is sometimes referred to as jargon, and this babble has a rhythm and tone which sounds a lot like adult speech.

After about a year of making various sounds and syllables, young children start to say their first word.

Tips to help you notice your child’s babble and know how to respond:

- Pause and wait for child to babble

- Observe your child so you can spot when they babble

- Copy your child’s babble – this supports them taking a turn, interact and pay attention to you!

- Interpret – say what you think they would say if they could e.g. baby says ‘babba’, but points or looks at the ball so you may interpret that they want to communicate ‘ball’ & say this back to them

Singing with babies is a fantastic thing to do!

Babies often respond to music and songs long before they can communicate with words, so singing together is a great way to build interactions.

Try these top tips when you sing:

- Sit where you can see each other’s faces

- Don’t go too fast – babies need more time to listen, so sing slow

- Pause as you sing – stopping to allow baby to react, by smiling, making sounds, actions or a word, helps to turn your singing into a mini-conversation

- Use actions when you sing – this will help babies focus on you; most babies will be able to join in with actions long before the words

- Repeat the same songs lots of times – you might get bored, but babies love to learn from repetition

- You can make up your own songs too, to match what you and baby are doing

- Don’t worry about what you sound like…… just have fun

We all learn new words all the time, even as adults! A good vocabulary is one of the most important things children can develop – it will help them to become more confident talkers, readers and writers.

When you come across a new word with a child, you can use these 5 steps to help them to learn what it means.

1. Make the new word Stand Out! Pause before or after the word, change your voice - this will draw the child's attention to the new word they heard

2. Use visual cues to build understanding. Use gestures, objects, pictures, facial expressions to help the child understand what the new word means

3. Explain what the new word means. Can you describe it? Does it belong in a category? Can you give more detail?

4. Link to things the child already knows. Link the word to recent experiences, existing knowledge or other similar words

5. Say it again! and again and again. Repetition is key - the more times the child hears the new word in different situations, the more they will understand it and eventually feel confident to use it.

In the early months of a new baby’s life, dummies can be a useful tool to help to soothe your baby if you choose to use one. It is useful to think about how you use a dummy with your baby in order to prevent any potential impact on their talking.

Can the use of dummies affect speech?

- There is various evidence about the use of dummies, although there is no current evidence that using them briefly during the first few months has a detrimental effect on speech.

- Longer term use of dummies (beyond one years old) and the excessive use of dummies has the potential to change tongue movements and the development of teeth, which may contribute to difficulties making certain sounds for talking.

- Children who use dummies frequently may also speak or babble less; having the dummy in their mouth may prevent them from practising babbling or talking.

Weaning babies off the dummy

- The NHS recommends weaning babies off dummies between 6 and 12 months of age.

- Weaning babies off the dummy by the age of 1 can allow them the opportunity to practice babbling and speaking their first words. Weaning your baby off the dummy allows them to become more expressive and to practice their sounds.

Top tips:

- If your baby is crying, try to think about what they are trying to tell you instead of reaching for the dummy; try using other comforting items such as a blanket, teddy or favourite toy.

- When your baby is content, ensure they don’t have access to the dummy – only use it when it’s needed.

- If your baby is trying to babble or talk, it’s important that you remove the dummy.

- Limit the dummy to key times such as bedtime or when they are poorly and stick to these times.

- Have a plan in mind for when you will stop using the dummy; you may choose to stop the dummy use at a certain time, or gradually reduce it.

- For older toddlers/children you could try swapping the dummy for something they would like, or giving it away (e.g, to Father Christmas, etc).

Chatting to your baby or child at mealtimes can make them feel more included, understand that mealtimes are a time to connect, and provide an opportunity to develop their conversational skills.

Try these top tips when you chat at mealtimes:

- Sit where you can see each other’s faces, so put your phones away, turn the TV off and give your child your full attention during these times.

- Name the foods and wait for baby or child to respond when you talk. If they babble, respond to them in turn by babbling back or saying something more about the food.

- You might say words like 'tasty', 'yummy' and 'sweet', words for textures like 'smooth', or even words for temperatures like 'cold'.

- Use words for actions too - both the things you're doing, using words like 'cut' and 'stir', and the things they're doing like 'eat', 'taste' and 'smell'.

- Offer your child choices of what they could eat by holding the objects up to choose from e.g. ‘do you want apple or banana?’.

- If your child is able or older, mealtimes maybe a great opportunity to discuss what has happened that day or any favourite conversational topic.

It’s never to early for sharing stories!

Sharing books and stories with your babies is a great way of connecting with your baby while you focus on something together.

It can support your little one to develop important skills, such as shared attention, interaction skills, listening and later beginning to understand and use the words they are hearing from you.

Take a look at some of our top tips and give them a try:

- Go slow! Give your baby plenty of time to look at the book and to respond to what you are saying.

- Sit so that you and your baby can see each other's faces.

- Use sounds and actions to help keep your baby's interest, if your baby makes sounds - copy them back!

- Repetition really helps your baby to begin to make links between what you are saying and what they see in the book - don't be afraid to share your favourites over and over!

Remember, it’s not always about reading the words - It’s about you and your baby sharing time together and communicating. If you have fun, baby will have fun and learn to love books.

Books and stories are a fantastic way of supporting young children’s language development.

Sharing books and stories with your children allows you to spend time together with a shared focus – this is really important for developing their listening and interaction skills.

Books are a fantastic source of new and interesting words and information! Whether your little one is just starting to talk or is a total chatterbox, there are always new words to learn and new things to talk about.

Top tips:

- Go slow! Take a pause before or after you turn a page, give your child time to show or tell you about something that has interested them.

- Sit so that you and your child can see each other's faces.

- Take time to talk about new words - help your child understand what they mean and then use them again and again.

- As children develop more language skills, talk more about the stories - talk about the characters, can you both work out what might happen next?, what would you and your child do if you were that character?

Remember, it’s not about reading every word or even every page. It’s about you and your child talking together and enjoying stories.

The best way to assist learning for young children is through social interactions with peers and adults. In order to make screen time a shared experience, a discussion topic, and an activity with boundaries, adults should make an effort to schedule time for activity sharing with their children.

What is screen time?

Screen time is considered anytime which is spent looking at a screen. Types of screens include: mobile phones, computers, tablets; including iPads and television. Screens can be used for a variety of reasons including looking at photographs, watching TV, looking at social media, watching YouTube videos, playing games and watching educational content

What are the risks involved?

It is known that children learn from interactions with those around them and when using a screen, these opportunities for interactions can be reduced.

- Screens do not respond the say way as humans and do not provide the same feedback. They do not respond to children’s attempts to communicate.

- Screens on in the background can cause disruption and can be distracting, this can have an impact on children’s play.

- Screens can mean reduced opportunities for learning and interactions with adults and peers.

Top tips:

- Reduce the amount of time your child spends with a screen.

- Be a good role model and limit your own use of screens.

- Share screen time. Watch together, interpret and with your child as you share the experience.

- Make it fun!

If you have concerns about how your child’s speech, language or communication is developing, you may find some of the information below helpful

Attention and listening

You may be concerned about your childs attention and listening skills if they demonstrate some or all of the behaviours described below:

- Appear to ignore you

- Cannot sit still

- Talk when they should be listening

- Cannot tell you what you have been talking about

- Do not appear to know what to do

- Can only concentrate on one thing

- Are easily distracted

- Do not settle with one toy, but flits from activity to activity

How can I help at home?

- Make sure you look at the child you are speaking to.

- Ensure you have the child’s attention BEFORE giving the instruction e.g. say the child’s name first and wait for them to look.

- Background noise, e.g. other people talking, television etc, is a distraction– try to reduce it where possible.

- Use short simple sentences with a familiar vocabulary and avoid ambiguous language.

- Introduce classroom rule such as Good Looking/Good Listening/Good Sitting/ Good Waiting.

- Keep tasks and instructions short. When they remember and follow the rules—make sure you remember to praise them.

- Set time limits for children to complete tasks (make these more than achievable to start with). Use a timer of some sort to help the children be visually aware of the progress of time e.g. sand timer.

- Write down your instructions for your child to remember (or get them to do it), or if reading/writing is tricky use pictures/ visual support.

- Offer forced choice answers, so instead of saying ‘what do you want for dinner?’ say ‘would you like chips or sausages for dinner?’

- Break long instructions into short steps.

- Give instructions in time ordered sequences.

- Slow down your delivery and use pauses. Allow time for slower responding pupils to process instructions/ questions.

- Be prepared to repeat or rephrase messages.

- Set the child manageable goals. Ensure previous task is completed before giving instructions for new one.

- Gradually increase the length of time you expect the child to work for.

Stage One (0-1 year):

Very distractible, attention is focused on whatever is their current interest and will be quickly shifted to any new stimulus e.g. noise or a something they can see

Practical ways to help:

- Use the child’s interests and incorporate these into the different areas of play e.g., Peppa Pig figures in the water tray, to keep their interest for longer.

Stage Two (1-2 years):

Can concentrate on a task of their own choosing. Children do not have the ability to focus on more than one task. It is difficult for an adult to direct the child.

Practical ways to help:

- Allow the child time to complete an activity of their own choosing.

- You will need to use the child’s name and/or a physical prompt such as touching their hand to gain their attention.

Stage Three (2-3 years):

Attention is still single channelled (Child can listen if they stop their activity and looks at adult). The child is now able to shift their attention away from the current task and then go back to the original activity with adult support.

Practical ways to help:

- Say the child's name before giving any instructions or expecting a response.

Stage Four (3-4 years):

The child starts to be able to control their own focus of attention. Children are now able to shift their attention to and from tasks more easily and require less adult support.

Practical ways to help:

- Let the child know when it’s time to listen.

- Use visual prompts such as hands in the air or clapping to gain whole group attention.

Stage Five (4-5 years):

The child is usually starting school at this stage. They can now perform an activity whilst listening to the teacher giving instructions. This is called dual channelled attention. Concentration span can still be quite short, however, children can cope with group situations.

Practical ways to help:

- Use an introductory phrase, gesture or non-verbal prompt before you start talking.

- Give information in a clear sequence.

- Encourage active listening.

Stage Six (over 5 years):

Attention skills are now flexible and sustained for lengthy periods. The child can integrate visual and auditory information with ease.

Practical ways to help:

- Encourage active questioning and processing of information.

Understanding language

Children who have difficulties with understanding language find it difficult to follow verbal instructions. They need help to listen and extra clues, such as, a gesture to help then understand. It is important to change your language to make it easier for your child to understand.

How can I help at home?

- Avoid lots of questions or trying to get your child to repeat words.

- Instead, comment on what she/he is doing, or what she/he is looking at, then pause (count to 5 in your head, or even 10 if you can bear it– it feels like a really long time!), this gives him/her a chance to comment too.

- Remember to repeat an instruction again if the child doesn’t follow it, make sure to wait 10 seconds before repeating; if they still do not follow the instruction then try rephrasing it to make it easier

- Use gesture, sign and/ or symbols as well as the spoken word when giving your child an instruction.

- Speak slowly.

- Emphasise important words that carry meaning, e.g. if you had a choice of 2 balls: ‘show me the big green ball’.

- Gain the child’s visual attention before speaking– call them by name, tell them to listen.

- Give instructions one step at a time. For example, “get your coat” - wait for your child to get their coat “now get in the car”.

- If your child does not yet understand any words, using objects of reference can help them. Choose an object to represent every part of your routine. Say the word ‘bath time’, show the object (a sponge), then guide your child through to the bathroom.

Auditory memory is considered to be a higher level skill, it affects all learning and language skills. It includes recalling information, and the order in which it is heard.

Characteristics of a child with auditory memory difficulties may include:

- Difficulties following instructions, particularly as length increases

- May only remember part of a long instruction

- Poor retention of words in songs

- Difficulty remembering sequences of information

- Confuses directions

How can I help at home?

- Allow extra time for your child to respond.

- Use short, simple instructions and breakdown longer instructions.

- Make sure your child is listening before giving any instructions.

- Use pictures or gestures when giving instructions.

- Give written or picture lists to support memory.

- If your child has not understood repeat the instruction in shorter bits e.g. change “After you finish your dinner place it in the sink and wash your hands” to “finish your dinner (pause), place it in the sink (pause) go and wash your hands”.

- Give instructions in the order they should be done.

General Strategies

It is probably not possible to ‘teach’ a better memory, but we can all learn strategies which help us to organise our memories better. Better organisation leads to more efficient recall, and better working memory skills.

- Rehearsal: Repeating the word or words over and over again under your breath or in your head.

- Visualisation: Many children have quite strong visual memories. Thinking in pictures is an excellent strategy. Another visualisation method is to remember a list of items by making a chain of links or story e.g. elephant, banana, chair, pig– the elephant is eating a banana, the banana is on a chair, the pig is hiding under the chair.

Using language

Your child has difficulties with their talking. This means:

- They are not using as many words as they should. For example they may just be making noises and not using any meaningful words

- Your child may be using some words but we want to encourage them to use more e.g. they may say “car” and we would encourage them to say something like “big car”

How can I help at home?

1. Be on the same level as your child when you are communicating with him/her. This refers to:

- The same physical level e.g. if he/she is lying on the floor– you lie on the floor; if the child is sitting on a chair– sit on a small chair as well

- The same language level– therefore you need to use short, simple, repetitive words or sentences, emphasising the key words when communicating with your child.

2. Follow your child’s lead. Communicate with him/her about what he/she is focussing on and focus on his/her interests within an activity. Try the following techniques:

- Watch what your child is interested in

- Wait to see if he/she attempts to communicate (wait for up to 10 seconds– this is a long time and will feel strange to begin with) to see if he/she makes any attempts at communication; (try to let the child take the first turn)

- Respond to any communication attempt, you may need to interpret their message. Be face-to face

3. Imitate: Copy your child’s actions, facial expressions, sounds, gestures, words etc. this is an excellent way to encourage your child to allow you to enter his/her play/ activity.

4. Interpret: Treat any sound, facial expression or gesture as if it was an attempt at communication. Copy it back to your child and give it meaning e.g. when your child looks at something, points and makes a sound to indicate that he/she wants it.

5. Comment: Comment on what your child is doing e.g. if he/she is splashing in water you say “splash” at appropriate times. If he/she is making up and down movements with a paintbrush you say “up”/ “down” as appropriate– this will be more meaningful for your child as you are commenting on what he/she is doing.

6. Avoid asking your child to say words.

Some children find it hard to structure and order their stories. These children may:

- Struggle to re-tell an event or story

- Muddle up their written stories at school

- Muddle up the order of events within their stories

- Not include all the information needed when telling a story (e.g. miss out who they are talking about)

How can I help at home?

1. Read stories regularly to provide exposure to stories and formal language

2. Teach your child ‘beginning, middle and end’ concepts Talk about these ideas in stories as well as in everyday activties.

3. Use scaffolding questions to help plan narratives:

- Who was there?

- What happened?

- When did it happen?

- How did she/he feel?

- What did she/he do?

- How did it end?

4. Practice retelling of events and life experiences

5. After a TV programme or DVD, talk about the story in this way too

6. Make your own story books.

Some children have difficulty in recalling/ remembering names of items and pictures. This can restrict their vocabularies and sentences. Children may present with word finding difficulty in one or more of the following ways:

- Hesitating to give him/her self more time to think of a word, e.g. “ we went to erm….”

- Substituting specific vocabulary for general filler words, e.g. “we went to that place….”

- Talking about the word rather than using a specific label, e.g. “we went to a place with swings and slides”

- Changing the sentence to avoid using the word, e.g. “ I played on the swings”

- Confuse words with similar meanings, e.g. “I went to the fair” (instead of park)

- Confuse the way words are said, e.g. “ I played on the round-around”

How can I help at home?

1. Time– where possible give your child plenty of time and reassurance to think of the word, e.g. “there’s no rush….I’m listening”.

2. Descriptions– encourage the child to describe the word, e.g:

- Does it belong to a group of things e.g. vegetables?

- What does it do?

- Where might you find it?

- Can you describe it?

- What does it look like?

- What else can you do like this?

- What else does it make you think of?

3. Sound cues– encourage your child to think about the following:

- Is it a long or short word?

- What sound does it begin with?

- Can you think of any other sounds in the word?

- Can you think of a word it rhymes with?

- Can you clap the number of syllables in the word?

Some children have gaps in their knowledge of words. They may present with some of the following behaviours:

- Slow to respond

- Quick to respond, but give an incorrect answer

- Say “I don’t know”

- Use “thingy” a lot

How can I help at home?

- Use real objects and model action words

- Use words that are appropriate to his level, e.g. car not vehicle

- Repeat key words and phrases several times within one situation. E.g. apples are juicy, the apple is red, I like to eat apples

- Use consistent labels– do not switch between words that mean the same e.g. ‘small/little’, or ‘cup/mug’

- Talk about the link between words. E.g. apples and pears are fruit, we eat them

General Activities

Look through a picture book talking about each picture, naming them and occasionally ask your child to find one of the pictures or try and name a picture themselves.

Play lotto by using two copies of a picture or bought picture matching games. Keep one set of pictures whole (to make boards) and cut the other set into individual pictures. Give your child a board, turn over a picture and encourage your child to try to match it to the board once you have named it. You take turns to turn the pictures and name them.

Extend this by keeping the picture hidden on your turn and encourage your child to find the picture on the board without seeing your card.

Turn an old box into a post box and encourage your child to post pictures you name in to the box. Or they can choose a picture, name it and post it.

Speech Sounds

Some children find it difficult to say some sounds correctly. They may change sounds for another or miss sounds off at the start or end of words. Children with speech sound problems may not know that they are saying words incorrectly. They may make mistakes with the sounds in words because they haven’t fully learnt the rules for using the sounds for speech.

How can I help at home?

- Let the child know that you WANT to understand them– show this by your body language and attention– be a good listener.

- Admit when you have not understood. Acknowledge the parts that you have understood and ask him/her to tell or show you the other bit again.

- Repeat the child’s sentence correctly to check you have understood and to provide a model for repeating the word back. Some children will copy, but do not put them under pressure to do so.

- Exaggerate the speech sound they are having difficulty with when you repeat it. This may help your child work out where they are going wrong e.g. “S...oap”.

- Be positive in your modelling and correction. Don’t say “its not a tat, it’s a cat, say cat” as this may confuse your child and they may not want to repeat the word again. Instead try offering a forced alternative question by asking ”Is it a tat or a cat?” If they have another go and get it right this time give them specific praise e.g. “yes it is a cat”. If they don’t have another try or do and still say tat, don’t worry just repeat the word cat clearly so they hear it again correctly and then move on with the conversation.

- Try to end conversations successfully, even when there have been parts you have not understood.

- Slow down- keep conversations at a slow pace.

- To help develop their awareness of sounds—go on listening walks around the house and outside. Listen out for all the sounds they can hear, (e.g. a car door shutting verses a bin lid closing; the distant sound of dog barking). See if they can tune in to these sounds, this will help them tune in to speech sounds which are harder to discriminate between.

- Pick a sound and look for all the items in the house which start with it, e.g. pan, peas, pots, perfume; playing I-spy with older children helps in the same way.

See videos below guiding you through how to achieve specific consonant sounds with your child. The Speech and Language Therapist Olivia is using an approach called Cued Articulation, where sounds are represented by signs. Your Speech and Language Therapist will let you know which sounds your child should be working on. Remember - children acquire sounds at different ages. Please see information on our website about speech sound development 'Ages and Stages' for further information.

Stammering

We see stammering as an acceptable and valid way of talking; there is nothing wrong with stammering, it is just a different way of talking. We understand however, that stammering can cause concern for parents and can impact a child’s or young person’s self-esteem and confidence. If parents are concerned, or a child or young person’s stammer is holding them back from doing what they want to do, or is causing upset and frustration, we are here to help.

Therapy for stammering is individualised for each person and usually depends on the child’s age and awareness. For younger children, we typically support parents and staff in nursery or school to learn more about stammering and how best to support their child at home and in nursery or school. We offer online workshops and sessions in clinic and will discuss your best hopes for therapy and collaboratively plan what support would be beneficial for you and your family.

For older children and teenagers, we continue to support parents and teachers, however, we may also recommend sessions with the young person. This may be individual or group therapy sessions. In these sessions, we work with the young person to problem solve how to make things more achievable and easier for them. We usually explore their thoughts and feelings about their stammer and support and empower children and young people to be confident communicators, regardless of their stammer

Stammering (also known as stuttering) isn’t caused by nerves or anxiety. It’s a neurological condition meaning it’s caused by the way the brain is wired and develops and is often related to the child’s language development.

Facts and figures:

- Between 5-8% of children will stammer at some stage, 3% will continue to stammer into adulthood.

- Stammering most commonly starts between 2-5 years. This is when language skills typically develop at a quick rate and children are starting to use longer words and speak in longer sentences. It means that there is added demand on the child’s still-developing speech motor system at this time.

- Stammering can also start later than this and it can start gradually or quite suddenly.

- Stammering usually varies a lot, from day to day and from situation to situation. This is because many different things, internal and external to your child, affect fluency of speech.

- There is no relationship between stammering and intellectual ability and stammering affects people from all walks of life.

- There are many, many highly successful people across the world who stammer.

Primary features of a stammer can include:

- Repetitions – this may be sounds, syllables, words, phrases. E.g. b-b-book, boo-boo, book-book

- Prolongations – stretching the sounds out. E.g. sssssssnake

- Blocking – getting stuck on a sound or word.

Secondary features of a stammer can include:

- Avoidance; Replacing words e.g. A child asking for a coffee at a café, because they feel they feel they will stammer on the intended word “milkshake”.

- Reluctant talking; e.g. Not responding when spoken to or asked a question. Pretending to have lost their voice so they don’t have to speak

- Body language: visible tension, head or body movements, grimacing, red in the face,shaking, clenching fists, harming themselves

Facts and figures taken from: Action for Stammering Children

There isn’t one specific reason a child stammers and parents do not cause stammering, however, there are some associated factors which may make it more likely for a child to stammer which include:

Genetics:

- Stammering tends to run in families. It is influenced by, but not completely explained by, genetics. There is ongoing research into this. There are likely to be several genes involved rather than one single gene.

Differences in Brain Development:

- Stammering can arise because the complex neural pathways involved in speaking develop slightly differently in people who stammer. Scientists have found subtle differences in the way that the parts of the brain involved in speaking interact and also some subtle structural differences. There is continued ongoing research into this.

Language and Speech Motor Skills:

- Learning to talk is one of the hardest things a child has to master and doesn’t always happen smoothly. Finding the right words to say and coordinating speech is very complex and requires the use of over a hundred different muscles, which puts a huge demand on the child’s developing brain.

Thoughts, Emotions and Temperament:

- Research into broader aspects of temperament suggests that some children who stammer experience emotions relatively intensely and find it harder to regulate their emotions. This is another area that is being investigated by researchers at the moment.

The following are general tips to help you to support your child:

- Give your child your full attention when they speak to you, so that they are not competing with others or with the television or radio.Competing with additional noise can be stressful for children who stammer

- Always look at your child when they are talking to you

- Let your child finish speaking, no matter how long it takes, without interrupting. Also support other family members not to interrupt

- Don’t speak for your child, let them say their own thing, in their own way and in their own time

- After your child speaks, pause before you respond

- Listen to what is said, not how it is said

- Speak to your child in a calm, slow, relaxed voice. In providing a good model for speaking by using quiet, unhurried speech and patient listening, you will reduce your child’s need to rush their talking

- Avoid making remarks such as: “Take your time” “Slow down” “Take a deep breath”. This draws attention to your child’s speech and places further demands on them while they are talking which may not be helpful

- Do not insist that your child repeat mispronounced words or grammatically incorrect sentences, instead, simply rephrase what your child said, using correct grammar and pronunciation. For example, if your child says “Sarah not g-g-g-going”, you can say “That’s right, Sarah isn’t going”

- Avoid putting your child on the spot by making them answer questions or talk in front of an audience of relatives or friends

- Remember, talking is not a test. Set aside some time each day when you can talk to your child in a relaxed situation. Some activities you could try include looking at books together, or playing a game together

- Be open with your child if you notice they are struggling. Many adults who stammer say they wish their parents had talked about it more with them when they were young. Talking about stammering can help to reassure the child and prevent any anxiety around speaking from taking hold. If your child’s stammer is easy and relaxed and they don’t appear to be aware they’re doing it, there’s probably no need to say anything about it at this stage

- Consider talking to your child about how they would like you to respond when they stammer

- Be mindful of the language you use around the child. Avoid using words like ‘bad’, e.g. “his stammer’s really bad today"

- Please remember, that no one is 100% fluent. We all sometimes hesitate, repeat parts of a message and stumble over our words

- Stamma - main homepage

- Palin centre

- Penguin app - The app aims to provide parents and carers with the awareness of how important they are in the early stages of stammering, how much they can influence by being aware of their own feelings around stammering, and how modelling what they instinctively know can be helpful, instead of instructing their child to make changes to his or her talking.” - The new ‘Penguin’ app for children who stammer - Action for Stammering Children . “The Penguin app is not a replacement for in-person speech therapy, but it could help parents learn how to support their children during this early stage. Parents don’t cause stammering and they are the best placed people to help their child enjoy talking” - penguin (benetalk.com). The app is suitable for parents of children who are 7 and under. The app takes you through 10 topics that you can work though on a daily basis. Each topic takes around 5 minutes. You can download this free from the app store.

-

Stamma - Information and support for people who stammer, parents, and families.

-

Stamma - Videos for parents about stammering and how to support your child who stammers